By USHA LEE MCFARLING / APRIL 28, 2020

Debbie Accad, 72, a clinical nursing coordinator for the Detroit VA Medical Center, died from complications of the coronavirus on March 30. Celia Yap-Banago, 69, a “fireball” of a nurse who worked for 40 years at a hospital in Kansas City, died last week. Both women were just weeks away from retirement.

Araceli Buendia Ilagan, 63, a nurse-manager in the surgical ICU, died March 27 at the Miami hospital where she had worked for 33 years. Also lost were Ali Dennis Guillermo, 44, a registered nurse who worked the night shift at Long Island Community Hospital and happily took on extra work for colleagues; Daisy Doronila, 60, a nurse at a New Jersey jail where inmates fell ill; and Noel Sinkiat, 64, who worked at Howard University Hospital for 41 years and had been planning the long motorcycle trip he was to take after his upcoming retirement.

As the coronavirus pandemic takes a devastating toll on health care workers, death notices published in recent weeks starkly show that it is hitting Filipino Americans — who make up an outsized portion of the nation’s nursing workforce — especially hard.

An estimated 4%, or about 150,000, of nurses in the U.S. are Filipino, but in some regions they account for a much larger share of caregivers. In California, for example, nearly 20% of registered nurses are Filipinos. And because they are most likely to work in acute care, medical/surgical, and ICU nursing, many “FilAms” are on the front lines of care for Covid-19 patients.

For Filipino families who have multiple members working in health care, the toll can be even more excruciating. The virus claimed the lives of both Alfredo and Susana Pabatoa, a married couple from New Jersey. Alfredo, 68, was a medical transporter, while Susana, 64, was an assistant nurse at a nursing home. They died in March, within days of each other. Luis Tapiru Jr., 20, died of the virus alone in his Chicago apartment on April 10, while his mother, Josephine, a nurse, was in an ICU in a coma and his father, who also worked part-time as a caregiver, was on a ventilator. She died four days later.

Filipinos are famous for, and justly proud of, their nursing acumen. The history of Filipino nurses in the United States is a long and complicated one, a symbiotic relationship borne of war and colonialism, and as some see it, racism and the exploitation of a critical medical workforce that has often been hesitant, because of cultural norms, to complain about poor workplace conditions. But some in the community are now speaking out.

“That Filipino American nurses should emerge as one of the key forces in fighting this pandemic is no surprise. It’s also no surprise that they are being exploited and not recognized,” said Emil Guillermo, a Filipino American journalist and executive director of the Filipino American National Historical Society Museum in Stockton, Calif.

One of those on the front lines is Gem Scorp, a 38-year-old registered nurse who came to New York from the Philippines in 2006. He has been caring for coronavirus patients in the ICU and radiology department of a Queens, N.Y., hospital for weeks. At the peak of the outbreak, Scorp was hearing 10 “code blue” calls each shift.

He had a fever and chills in March, but with so many patients flooding the hospital, he said he was told to continue working unless he was critically ill. He finally was tested for the virus and found positive April 14. Now symptom-free, he has continued living with other health care workers in a “Covid hotel” to protect his family. He has not seen his wife or his 4-year-old son for weeks.

Scorp is heartbroken, tired, and distraught over the loss of dozens of patients. “I’ve never seen so much death,” said Scorp, who has worked as a nurse for nearly two decades. He has also grown frustrated about what he sees as the unfair workload and lack of recognition for Filipino nurses. While these are things he has accepted for years, Scorp said the pandemic has brought the issues to the surface.

He does not want to criticize his fellow nurses. He understands all nurses are strained by the pandemic in different ways and says that many nurses, of all ethnicities, are acting heroically. But the virus has laid bare some uncomfortable and longstanding racial tensions in nursing, he said. What he sees is Filipino nurses continuing to go unnoticed even as they take on the most dangerous and wrenching tasks in Covid-19 units, like bathing or suctioning intubated patients and comforting and holding those who are dying without family present.

“Have you seen any Filipino nurses complain? Have you seen any Filipino nurses crying on TV? No,” said Scorp. “Why? While all those other nurses are busy doing videos and getting all the credit, Filipino nurses are the ones risking their lives trying to save Covid patients.”

“Our enemy is the virus, not other nurses, but this is what I am seeing in my own experience,” he said. “At the time when no PPE was provided, it was Filipino nurses doing the job because, as you know, we are born risk takers when it comes to performing our duty and our calling.”

Filipino health care workers say the coronavirus, with its high death toll among the elderly, has been particularly hard on them because many live in multigenerational households.

That’s true for Patrick Tabon, an assistant professor of clinical pharmacy at the University of Southern California who works in various USC hospitals and clinics. He usually supervises the medications and care of his grandmother, 83, who has heart failure and diabetes and requires dialysis several times a week. Tabon hasn’t seen his grandmother since February; the family had to hold their traditional Easter dinner over Zoom.

“Knowing my risk as a health care worker, I’m just really afraid I will pass it on,” he said. “You have to sacrifice family, and that’s really a big thing for us. If this drags on for weeks or months, it will really make me anxious.”

Many FilAm nurses also work extra shifts to support their families and send money back to relatives in the Philippines. Those extra hours, and extra exposure to patients, mean higher risk. “We are all scared,” said Scorp, who works seven days a week in two jobs. “We are not afraid to die,” he said, “We are afraid that if we die, who will take care of our families here and back home?”

It’s the lack of proper masks and other personal protective equipment that has pushed some Filipino nurses to speak out, when in the past they stayed silent about their working conditions. Some are wearing homemade masks. Nurses said they also have resorted to buying their own PPE on Amazon, bartering for it within their personal Filipino nurse networks, or simply working without the proper gear, even intubating Covid patients wearing just surgical masks.

Those risks are completely unacceptable to Zenei Cortez, an RN who works at Kaiser Permanente’s South San Francisco Medical Center and, as co-president of the California Nurses Association/National Nurses United, is the first Filipina to lead a major U.S. labor union.

In four decades of nursing, Cortez has treated patients with AIDS, SARS, and Ebola, but always received proper PPE, she said. With coronavirus, she said, many nurses are not being provided with the N95 masks they need. While Cortez speaks for all nurses in her role as a union leader, she said she worries that her fellow Filipino nurses are less likely than other nurses to demand workplace protections.

“Culturally, we don’t complain. We do not question authority,” she said. Many Filipino nurses feel a strong sense of group loyalty, or the importance of putting the welfare of the group over that of the individual; in Tagalog, the word is pakikisama. “We are so passionate about our profession and what we do, sometimes to the point of forgetting about our own welfare,” she said. “We treat our patients like they are our own family.”

Cortez is heartened by the response she sees among some young Filipino nurses. “What I am seeing now is that my colleagues who are of Filipino descent are starting to speak out,” she said. “We love our jobs, but we love our families too.”

One of those speaking out is Allison Mayol, a 23-year-old Filipino American nurse who has been treating patients with coronavirus at a Santa Monica hospital. She spent the one-year anniversary of her first nursing job on suspension, however, for questioning the hospital’s refusal to provide N95 masks to nurses working with Covid-19 patients. One nurse in Mayol’s unit has contracted the virus. In statements, hospital officials said they were following CDC guidelines and were now providing N95 masks to all nurses treating Covid-19 patients.

Mayol, who has been reinstated but is continuing to protest the written warning placed in her personnel file, said it had been a difficult decision to speak out. “It’s easy for me to push my needs aside to take care of my patients,” she said. “It’s a struggle for me not to feel selfish for standing up for my own health in the middle of this.”

It is this particular combination of qualities — selflessness, commitment, dedication to patients, deference, and bayanihan, a kind of communal spirit — that makes Filipinos such good nurses, but it is also putting them at higher risk of infection from the coronavirus, said Leo-Felix Jurado, an RN who chairs the department of nursing at William Paterson University in New Jersey and serves as the executive director of the Philippine Nurses Association of America. Jurado said many of the members of his association had contracted the virus, including the president Madelyn Yu; her husband, 67-year-old Alfredo Yu, was also infected and died last week. “Nursing is the opposite of social distancing,” he said.

“You see that in the literature, Filipino nurses are preferred because they work hard and don’t complain,” said Jurado, whose dissertation included a detailed analysis of the work habits of Filipino nurses. “It’s a calling. They do it with a love and sincerity that was ingrained in them.”

That calling definitely gets noticed. “All of my nurses are amazing, but Filipino nurses do have the culture where their patients always come first,” said Annette Sy, who oversees 1,500 nurses (25% of them Filipino) as the chief nursing officer for Keck Medical Center of USC and who is married to a Filipino physician. “I have Filipino nurses who are in that protected category, above 65 years of age, who could stay home and I wouldn’t question it, but they say, ‘I have to be here to help my patients.’”

The Philippine connection to nursing has deep historical roots. A Spanish colony for hundreds of years (named after Spain’s King Philip II), the Philippines became a U.S. colony in 1898 at the end of the Spanish-American War. The roots of Filipino nursing began after U.S. Army personnel started training Filipinos so they could provide care to American soldiers. Offering a full American nursing curriculum and English lessons, they created a powerful educational framework that allowed the country to become the world’s leading exporter of professionally trained nurses. For many Filipinos, the white nursing cap is a powerful symbol of a path to a better life.

But many Filipino nurses feel they are treated as expendable even though their large numbers and work ethic, they say, keep the American health care system functioning. Many also complain about “the bamboo ceiling” that until recently kept Filipino nurses out of positions of leadership. Over the years, immigration rules have waxed and waned, allowing nurses to immigrate to the U.S. but only when the need for them arises. “Every time there is a nursing shortage, where do they go? The Philippines,” Jurado said. “When there is a need for them, they open the immigration gates. When there is no need, they close the gates.”

The pandemic has many Filipino nurses so profoundly sad, many said, because they hate losing patients. “When someone dies on their shift, they take it personally,” said Guillermo. “They almost want to take the dead body, put it over their shoulder, and will it back to life.”

Scorp agreed. “We have big egos because this is our forte,” he said. “For us, every single death is a failure.”

Gem Scorp in Queens, N.Y., where he works as a nurse and has been treating Covid-19 patients. Originally from the Philippines, he came to New York in 2006. MONIQUE JAQUES FOR STAT

Zenei Cortez is co-president of the California Nurses Association/National Nurses United. COURTESY CALIF. NURSES ASSOCIATION

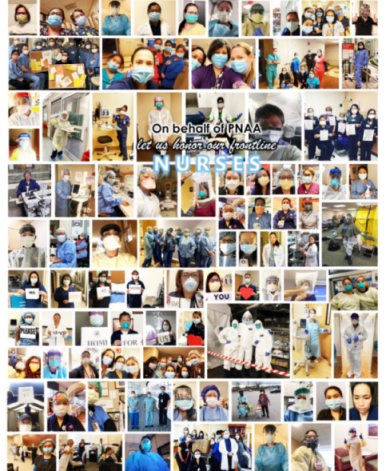

A tribute to nurses caring for coronavirus patients posted on the website of the Philippine Nurses Association of America. PHILIPPINE NURSES ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA

VIA Times – May 2020 Issue Vital News, Vibrant VIews for Asian Americans in Chicago & Midwest

VIA Times – May 2020 Issue Vital News, Vibrant VIews for Asian Americans in Chicago & Midwest